A Prussian fragment usually forgotten by linguists

Letas Palmaitis

In 1331 the Teutonic Order aimed to subdue Poland with the help of the Czechs. The Czech Army of Jan of Luxembourg was going to join the army of the Teutonic Order at Kalisz on September 21. The German army under the leadership of Otto von Lutterberg, Commander of Helm, and Marshal Dietrich von Altenburg crossed the Vistula on September 12. It consisted of ca. 8,000 soldiers (200 knights, 2,500 heavy cavalry, about 5000 light cavalry and infantry). On their way to Kalisz the Germans plundered, and set fire to, many villages and towns, including Sieradz, Uniejów, Łęczycę, Spicymierz, Wartę and Szadek. In Sieradz an incident occured with Hermann von Oettingen, Commander of Elbing, as related by historian Jan Długosz:

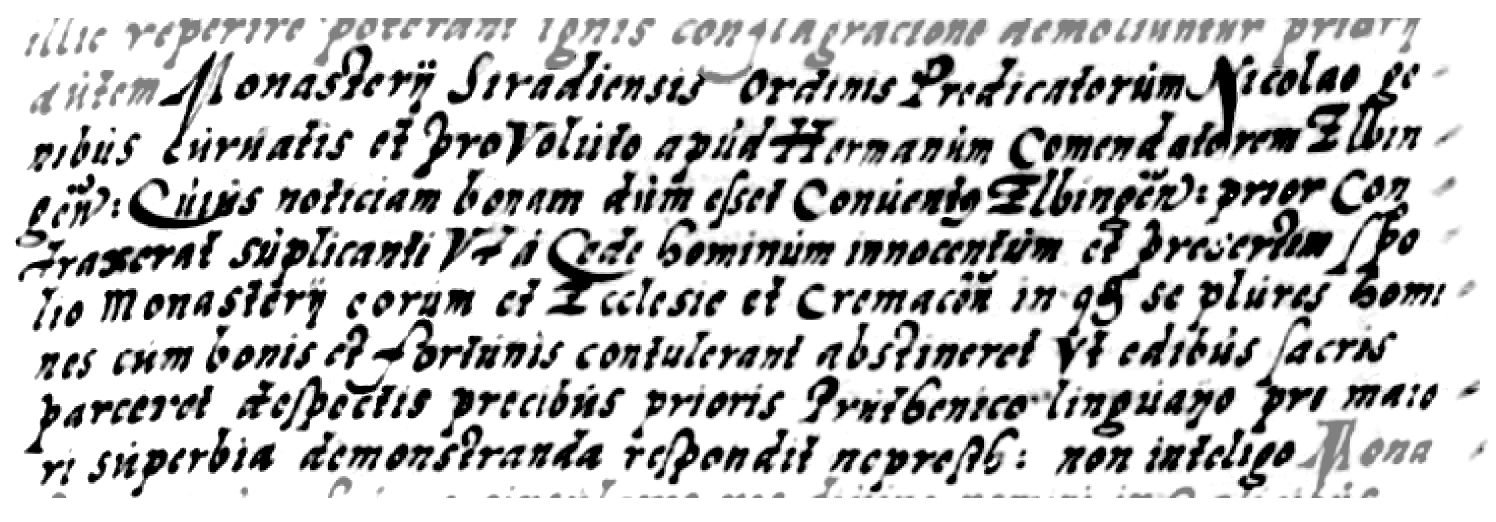

Monasterii Siradiensis Ordinis Predicatorum Nicolas genibus curuatis et pro voluto apud Hermanum Comendatorem Elbingensem: cuius noticiam bonam dum esset Conuentis Elbingensis: prior contraxerat[:] suplicanti ut a cede hominum innocentum et presertim spolio monasterii eorum et Ecclesie et cremacione in [25] se plures homines cum bonis et fortunis contulerant abstineret ut edibus sacris parceret despectis precibus prioris Pruthenico linguario pro maiori superbia demonstranda respondit nepresth: non inteligo.1

Nicolas, prior of the Dominican Order in Sieradz, on bended knees and groveled before Hermann, Commander of Elbing, with whom he had been on good terms earlier as a prior in Elbing. He begged him to refrain from murdering innocent people, especially from burning down their monastery and their church, where many people had gathered with their things and belongings, as well as to spare sacred edifices. Having disdained the plea of the prior, he answered in Prussian language to show greater superiority “Neprest – I do not understand you”.

This fact shows that even the German nobility was familiar with the Prussian language. Free Prussian warriors witings were participants of the same campaign of 1331. This explains why Hermann von Oettingen “remembered” the Prussian language in Sieradz, when he saw his acquaintance, the prior Nicolas, who could understand his words. This shows that the ban for knights' speaking Prussian could not always be observed, and not everywhere.

As for the expression “Nepresth”, it roughly corresponds to the epoch and place where the Elbing Vocabularly originated. The absence of the personal ending points to an apocopated form which, in all probability, is 3rd person. Material of the Elbing Vocabulary bears a testimony that short vowels were preserved in the final position in that dialect - cf. e.g. Nom. Sg. of i-stems like antis E 720, ausis E 525, dantis (< consonantal stem) E 97. Thus the reconstruction of the form in question should be *nē presta, which is a sta-present indicative form of the verb *pret- ‘to understand’ (cf. infinitive issprestun III 133 ‘to understand’ with the prefix *iz-.

This finally refutes Vladimir Toporov's doubts concerning the origin of the vocalism e of this verb in the 3rd Catechism (cf. e.g. also isspresennien III 77, issprettīngi III 95, poprestemmai III 95, etc.). Vl. Toporov says that the vocalism e may either reflect Baltic a, as in East-Baltic Lith., Latv. prat-, or it may also reflect ancient Indoeuropean e, as in Latin inter-pres.2

We should be grateful to Hermann von Oettingen, prior Nicolas and Jan Długosz for this confirmation of a conclusion reached by Vytautas Mažiulis: Pruss. *pret- goes back to Baltic-Slavic *pret- ‘to accustom, to be accostomed to’ deriving from an underlying Baltic-Slavic “present” stem *pret- ‘accustoms’, which existed in parallel with a “perfect” stem *prat- ‘is accustomed to’. The East-Baltic stem originates from the latter form.3